Open Source, Open Mind: The Cost of Free Software

Dylan Beattie, June 2024

There’s an emotional cycle that I’m sure most of you folks in this room can relate to. It starts with desire. You see the latest new thing - a smartphone, a laptop, maybe even something as apparently mundane as a new text editor - and you need it, because it is shiny and if you don’t have it you will never be happy. Then comes the installation. Whether you’re unboxing a new gadget, or installing a new app… you know that feeling. “I wonder what it can do?”

Then comes doubt. The website said it could play MP3s but I can’t see an audio player here anywhere. The sales tech said we could deploy custom workflows from GitHub but all I can see is the XML Upload button.

Finally, the moment of reckoning. The moment where you realise that your new gadget doesn’t quite do what you want… but it could. It’s got all the right bits, they’re just not quite configured the way you want them. You just need to hack it a bit.

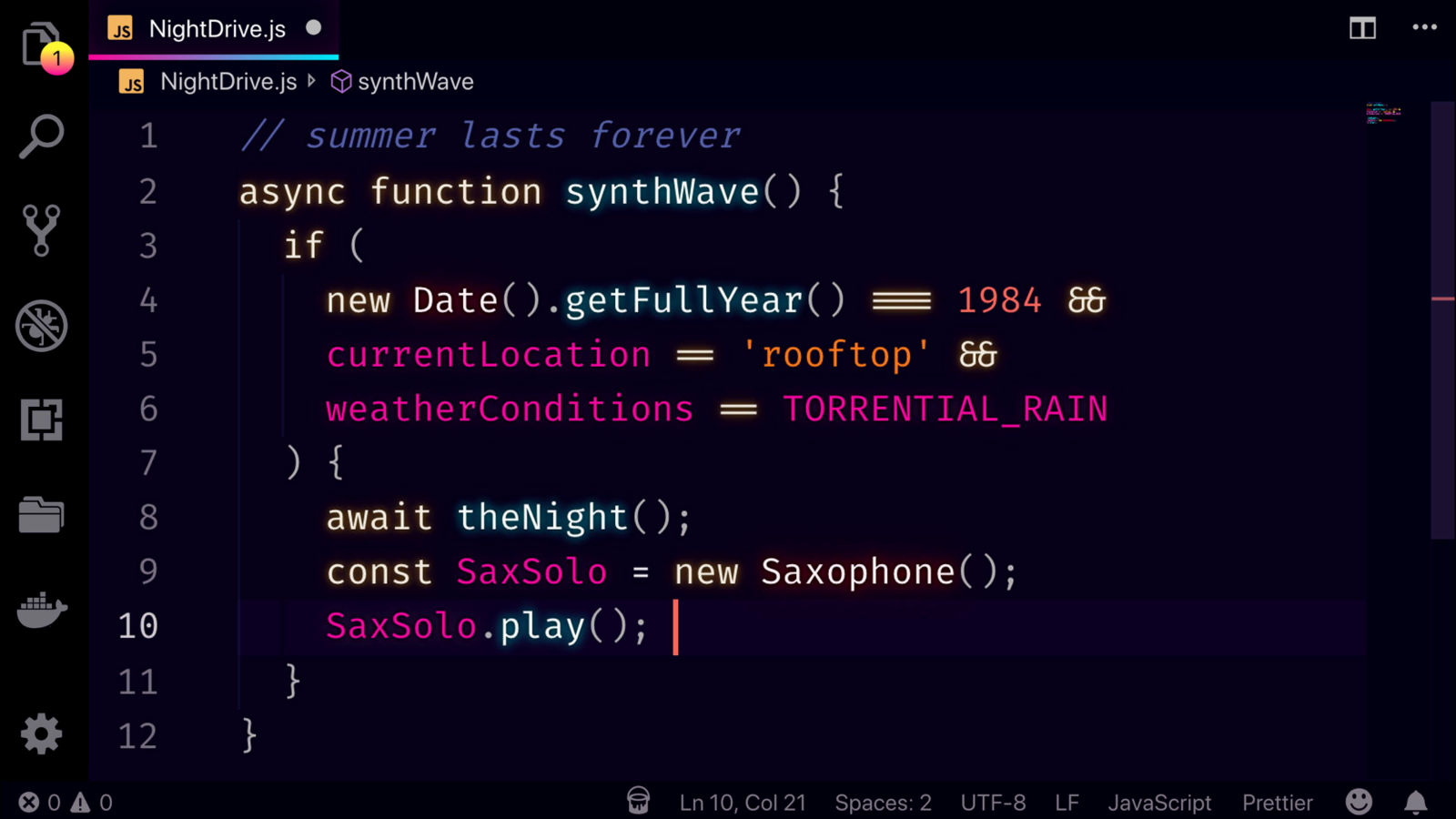

Sometimes, this is the start of a beautiful, creative synergy between human and machine. All you folks out there who have your IDE set up just the way you like it - your shell, your fonts, your colour schemes, your plugins… you know what I’m talking about here. To me, that’s one of the defining characteristics of a true hacker: if something doesn’t work they way they want it to, they don’t demand a refund, or open a support ticket… no, they roll up their sleeves and get to work. And to that kind of hacker, the worst thing you can possibly do is tell them no. No, you’re not allowed to change that - not for any technical reason; you’re not allowed to change it because we said you’re not. It’s against our policy. It’s against the law. It’s not allowed unless you give us more money.

In 1980, the folks at Xerox donated a laser printer to the Artificial Intelligence laboratory at MIT, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Xerox and MIT were both a really big deal in the early days of computer science: Xerox came up with dozens of astonishing innovations and utterly failed to turn any of them into viable products, which is why fifty years later they’re still stuck making photocopiers. MIT, on the other hand… MIT produced LISP, fax machines, passwords, ethernet, email, the Apollo 11 guidance software, RSA cryptography, spreadsheets, blockchains, the Roomba - and, maybe, free software.

You see, the new laser printer had a problem: it was built around the same printing engine as Xerox photocopiers, and it was prone to jamming. Now, when a photocopier jams - just to check: you folks know what a photocopier is, right? - it jams right there, while you’re stood in front of it making your copies. So you swear and maybe kick it a bit, and then open up the side and find that sad-looking crumpled bit of paper, and gently tease it out of the print rollers, and then close the lid and hopefully it all starts up again.

But a network printer? That’s on the other side of the building. So you send your print job, and then next time you go to get a cup of coffee you swing by the printer to pick it up… and discover the printer’s jammed. And it isn’t jammed on your job: it’s been jammed all morning. So you unjam it, and you go back to your desk, and when you come back a bit later you find it’s jammed again…

One of the folks working in the MIT lab at the time was this guy: Richard Stallman. The way Stallman tells the story, he wanted to modify their new laser printer, so when it jammed, it would notify everybody who was logged into the network, so whoever was nearby could go and clear the jam right away. So he asked Xerox for the source code for the printer’s operating software - and they said no. They refused to let him have it.

According to one interpretation, this incident galvanised Stallman into dedicated the rest of his life to promoting free and open software. Another interpretation is that it pissed him off so much he’s still angry about it over forty years later. I suspect both interpretations are true, but Stallman has spoken multiple times about that Xerox printer incident and said that was what inspired his commitment to free software activism over the next few decades.

Before we go any further, it might be a good idea to talk about what we mean by “free software”. There’s historically been a distinction between “free as in free beer” and “free as in free speech”, so let’s talk about free as in beer first. Beer’s actually a really good example of a particular kind of free: somebody gives you a free beer. Yay, because you didn’t pay money! Now you can enjoy all the wonderful things you can do with beer, like drinking it. Except maybe you can’t drink it, for medical reasons, or religious reasons, or because you’re driving, or because you’re twelve. You can’t keep it – not forever, it’ll go bad after a while. You can’t sell it, because in most countries it’s illegal to sell alcohol without a license. Free here is all about price, and nothing to do with freedom… and most of the time, when normal people talk about free software, they mean free as in free beer. Spotify, YouTube, Google Drive: the world is full of incredibly successful software that doesn’t cost any money, but which seriously restricts what you can do with it.

Let me ask you folks a question: how many of you own any second-hand computer software? How old is it? These days, you never really own computer software, so the idea of selling it second hand doesn’t really compute, but there’s loads of listings on eBay for vintage computer software – because in the days before the internet, when software came in cardboard boxes, it was much easier to think of a program or a game as a physical thing.

Any of you folks remember these? Games cartridges: a chunk of plastic with all the code to Sonic Hedgehog burned into it… you know infrastructure as code? This was the complete opposite: code as infrastructure. And because the code was so inextricably coupled to the physical package, when you finished Sonic Hedgehog, you could treat that cartridge like a commodity: sell it, lend it to your friends, rent it out. We’re talking the late 1980s through the early 1990s here, when I was a teenager in the UK, and at my school there were the console kids and the computer kids. The console kids had skateboards, and shaved their heads, and were usually in trouble at school for setting stuff on fire. The computer kids had mountain bikes, and long hair, and we also set stuff on fire but we were usually smart enough not to get caught. And when it came to video games, we had the Atari ST, the Amiga 500, the IBM PC… and piracy. Yarr. If I wanted to play a new computer game, I had a choice. I could buy it. Boxed games like X-Wing, or Eye of the Beholder, or the Secret of Monkey Island, retailed for between thirty and forty pounds. The same as buying twenty Big Macs, or a new pair of jeans.

Or I could copy it. Copying software was ridiculously easy, especially if your PC had two floppy disk drives… and if it didn’t, MS-DOS included a command called diskcopy that would prompt you to keep swapping disks until the copy was done. Because copying the actual games was so easy, lots of those games included some kind of copy protection system: you’d have to type in the 25th word on page 19 of the manual, or use your cardboard Secret Decoder Ring to find the correct symbol to click on. Other publishers tried to exploit quirks in the IBM PC floppy disk controller to make un-copyable disks - in the days before device drivers, it was relatively easy to make hardware do all kinds of weird things that weren’t in the spec, like putting hidden sectors on a disk which the diskcopy tools couldn’t see. Copying games was definitely illegal, and if you made a hundred copies of X-Wing and sold them at your local computer fair for ten quid each it was just possible the police might take an interest… but schoolkids swapping copies of Lemmings and Monkey Island with dog-eared photocopies of the instruction manual? We’re not exactly talking organised crime here.

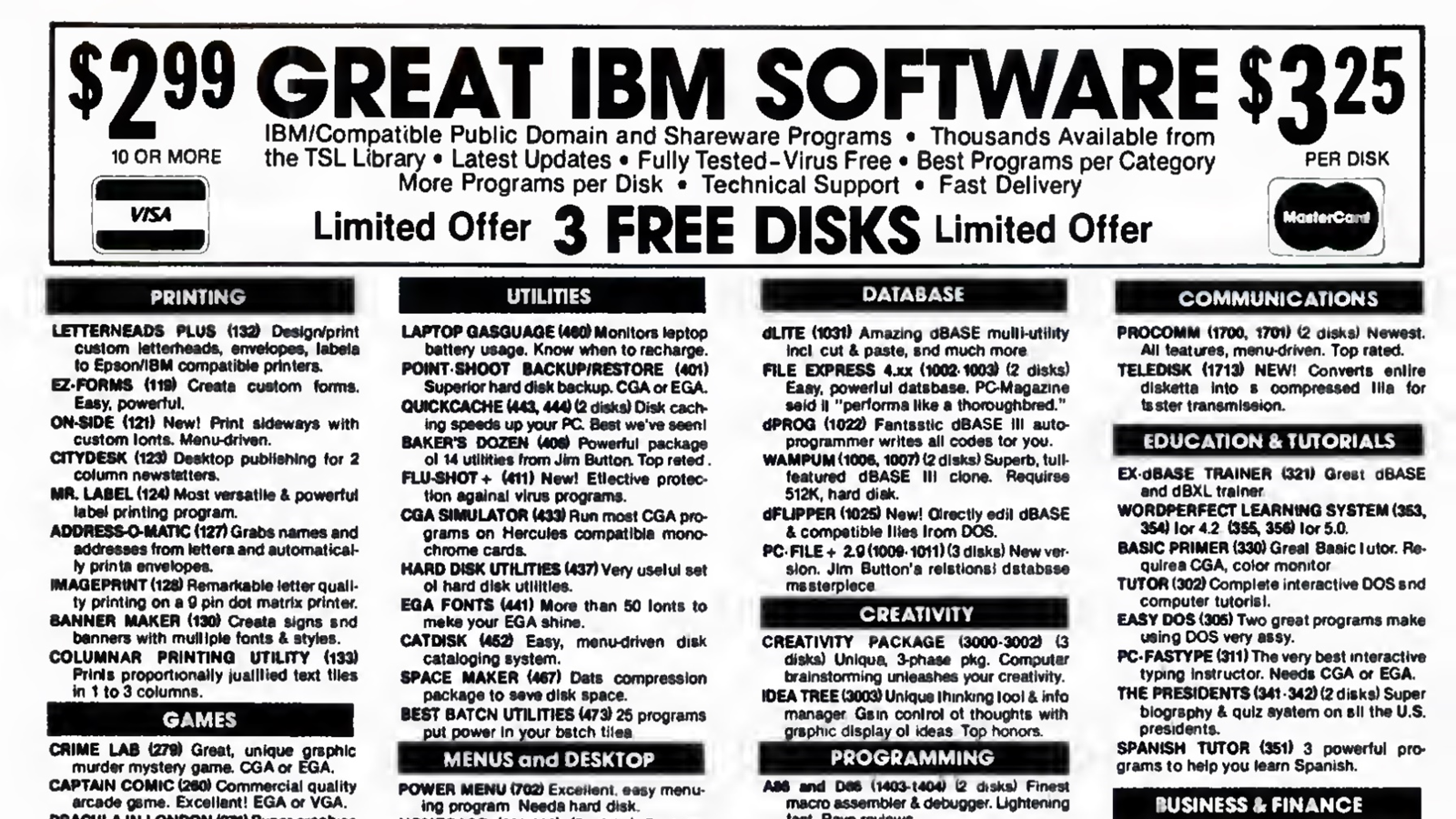

There was a third option, though. In the classified adverts at the back of the computer magazines were companies that sold free software. Games, utilities, programming tools… mostly developed by enthusiasts, in their free time. The software itself was free - as in beer. If you had a modem, you could download it from a bulletin board service. If you knew somebody with a copy, you could ask them to copy it for you - or you could pay somebody to copy it onto a disk and send it to you in the mail. This was completely legal: everybody understood you weren’t buying the program itself, you were paying for the disk and the postage.

Some software was in the public domain: the authors had waived any copyright over it. Most if it was something called “shareware”: the author included a README file on the disk with their home address and a note saying “this is free, but if you like it please send me some money”. Some shareware was “try before you buy”: cut-down or restricted versions of the full program which you could get by mail order.

But probably the most successful variant of the shareware model was the one pioneered by this guy: Scott Miller, the founder of Apogee Software. Scott had created a game for the IBM PC called Kingdom of Kroz. Episode 1 was released as shareware, and when you completed it, a screen popped up: if you wanted episodes 2 and 3, send a cheque to this address… and it worked. Kingdom of Kroz made nearly a hundred thousand dollars.

A few years later, Scott Miller got hold of a game called Dangerous Dave, created by a group of developers working at Softdisk, a games publisher in Louisiana: John Romero, John Carmack, and Tom Hall. They called their group “Ideas from the Deep”, and they’d figured out a way to do smooth scrolling graphics on the IBM PC, something nobody had ever done before.

They’d created a PC port of Super Mario Bros 3, which they sent to Nintendo - and as John Romero tells it, “they told us good job, and you can’t do this.” - the last thing Nintendo wanted was kids swapping 3.5 floppy disk copies of Super Mario instead of buying Nintendo games consoles. Scott Miller suggested that they use their new coding techniques to create an original game, and Apogee would publish it using the same model as Kingdom of Kroz: give away episode 1 for free, and charge for episodes 2 and 3.

That game was Commander Keen: Invasion of the Vorticons - the story of an eight-year-old genius who has to recover all the stolen parts of his spaceship from Mars, armed with a pogo-stick and a football helmet. Apogee published Commander Keen in December 1990; it made thirty thousand dollars in two weeks, enough to persuade Tom Hall and the two Johns to quit their jobs at Softdisk and start their own company: Ideas from the Deep became IFD, and then ID, and then just id. id would go on to develop some of the most successful and influential games in history.

That game was Commander Keen: Invasion of the Vorticons - the story of an eight-year-old genius who has to recover all the stolen parts of his spaceship from Mars, armed with a pogo-stick and a football helmet. Apogee published Commander Keen in December 1990; it made thirty thousand dollars in two weeks, enough to persuade Tom Hall and the two Johns to quit their jobs at Softdisk and start their own company: Ideas from the Deep became IFD, and then ID, and then just id. id would go on to develop some of the most successful and influential games in history.

Wolfenstein 3D pioneered the 3d first-person shooter. In December 1993, Doom introduced the world to networked multiplayer gaming - and took down just about every college network in America as students rushed to download it and then challenge each other to deathmatch games over the network. And in 1996, Quake was the first truly 3D first person shooter - and one of the earliest games to take advantage of the dedicated 3D accelerator hardware like the 3Dfx Voodoo. Those games all used the Apogee model: the first episode was free, and you had to pay for the rest - but the way you got hold of each free episode reflected a paradigm shift in the way software was distributed.

I got Wolfenstein 3D free on the cover of PC Format magazine; I copied Doom from a friend at college who had a modem, and I downloaded Quake from the idsoftware.com website using Netscape Navigator, because for me, and for a lot of people around the world, this point in history - 1996, 1997 - was the moment we got connected. We got a dial-up modem, installed a web browser, set up our first email address, and never looked back… and in the process, we found out that there was already a thriving digital community of hackers and activists who’d been online for a lot longer than we had, and some of those folks had some very specific ideas about what free software meant that had nothing to do with giving it away on the cover of PC Format magazine.

Turns out that, while the rest of us were setting up our dial-up modems and playing Doom, there was a thriving digital community of hackers and activists who’d been working towards a very different kind of free software. Software that embodied what they called the four essential freedoms:

0: The freedom to run the program however you want, for any purpose

1: The freedom to study how the program works, and modify it do to what you want

2: The freedom to distribute copies

3: The freedom to share your own modifications

These were, and are, the philosophy underlying the GNU project, set up by Richard Stallman in 1983 with the explicit goal of developing a completely free Unix-compatible operating system: an operating system kernel, text editor, a shell, a C compiler, linker, assembler - a critical mass of tools and utilities that the community could then use to build whatever other pieces were missing: spreadsheets, graphics tools, networking utilities. GNU software was coordinated and distributed via the internet: mailing lists, Usenet groups, bulletin boards and FTP servers - and, unlike most shareware and public domain software, it was distributed as source code, with the expectation that users would compile it themselves for their own hardware. By 1991, the GNU project had almost created a complete operating system: all they were missing was a working operating system kernel. Which is a bit like saying you’ve almost built a car: you’ve got wheels, seats, windows, a stereo, a gearbox… you just haven’t quite figured out how to do the engine yet.

Perhaps more significantly, though, they had created and published a document called the GNU General Public License, or the GPL, which codified the four essential freedoms into a format that, if necessary, could be enforced by a court of law.

Then in 1991, Linus Torvalds, a 21-year-old student at the University of Helsinki, announced on Usenet he was working on a “free operating system - just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones”, and uploaded the source code for his kernel to the university’s FTP server. By December, the combination of Linus’ “Linux” kernel and the GNU tools was self-hosting - you could use it to compile itself - and Linus had published his code under the GNU Public License; for the first time in history, there was a complete, working computer operating system that contained no proprietary code, copyrights or patents, and which was distributed under a license agreement that guaranteed its users the freedom to run it, modify it, share it - even sell it, as long as they didn’t try to impose any restrictions on the customers they sold it to.

This is probably an interesting time to ask the big question: why? What motivated all these people to publish their code without demanding payment in return? I think it’s fair to say that every single person we’ve met so far in this talk is, first and foremost, an enthusiastic hobby programmer. A hacker. Somebody who delights in the craft of programming, and relishes the challenge of translating the ideas in their head into executable code.

So how did they choose what to work on - and why, when they were done, did they release it for free?

For Linus Torvalds, I honestly believe he wrote the first Linux kernel just for fun, to see if he could, and had absolutely no clue that his student hobby project would end up powering half of the internet and a few billion Android smartphones.

For the folks at id software, they wrote the games they wanted to play. It’s that simple. I saw a talk by John Romero at an event in Berlin last year, and watching him talking about working on Doom and Quake, it was obvious that he and the rest of the team at id loved video games - and to them, the shareware model was just the best way they found to generate sales, make money, buy better computers, and use them to write, and play, more games. The fact they ended up so rich half of them went out and bought Ferraris didn’t really change a thing: most of those folks still write code every day, because that’s just what they do.

For Stallman and the GNU project, though, software was the executable expression of an ideology: free software driven by the fundamental belief that free software makes the world a better place. The problem is, as we’ve learned over and over again during the last quarter century: free software doesn’t pay the bills.

You might also have noticed that we’re almost halfway through this talk, and I haven’t yet mentioned the phrase “open source”… and the reason is that, by this point in history, the late 1990s, that term didn’t exist yet. The success of the world wide web had seen a massive spike in demand for server-capable operating systems – any of you folks ever try running a public website on Windows 95? Yeah… not a great experience - and if your company wanted to set up a web server, or an email server, or a database, you could do the whole thing without spending any money - as long as you had the time and the expertise to do it.

Most companies didn’t. They wanted to buy something that would just work, and have a phone number they could call if it didn’t. Companies like Red Hat and SUSE saw an opportunity here: they could sell free software! Download all the sources, compile them, put them on a CD-ROM in a nice box with a printed manual, maybe throw in a year of technical support… the problem was that word “free”. Companies struggled with the idea of paying money for “free software”, and there was clearly a significant gap between the hardline definition of “free” adopted by the GNU project and the closed-source proprietary model used by companies like Microsoft. When Netscape announced plans to release the source code to their Navigator web browser in 1998, it galvanised the community into coming up with a better term. One of the key players in that movement was Christine Peterson, the founder of the Foresight Institute.

As Christine describes it: “we discussed the need for a new term due to the confusion factor. The argument was as follows: those new to the term “free software” assume it is referring to the price. Oldtimers must then launch into an explanation, usually given as follows: “We mean free as in freedom, not free as in beer.” At this point, a discussion on software has turned into one about the price of an alcoholic beverage. The problem was not that explaining the meaning is impossible—the problem was that the name for an important idea should not be so confusing to newcomers. A clearer term was needed. No political issues were raised regarding the free software term; the issue was its lack of clarity to those new to the concept.”

Christine suggested the term “open source” at a meeting in February 1998; a few days later, Eric Raymond and Bruce Perens set up the opensource.org website. Netscape began referring to their forthcoming code publication as “open source”, and an event in April 1998 organised by Tim O’Reilly as a “free software summit” soon became known as the “open source summit”. Open source wasn’t just about avoiding the word “free”, though. It was about addressing a complex, but legitimate, concern that was beginning to get a lot of traction in the industry.

The GNU General Public License is sometimes referred to as a “viral” license, because of a clause in that license which specifically requires you to make the source code to any distributed derivative works under the same license.

If I release my code into the public domain, I waive any future copyright claim I have over that code. If I contribute code to an open source project that requires a contributor license agreement, a CLA, then I transfer ownership of my contributions to the legal body named in that CLA - if any of you folks here have contributed code to the .NET runtime, you’ll have signed a document transferring ownership and copyright of that code to the .NET Foundation.

If I publish code under the GPL, though, I do not in any way relinquish my legal rights as the author of that code. I still own the copyright. If I contribute one line of code to the Linux kernel, that line of code is mine, I own it, and I choose to make that work available to you under the terms of a license. If you modify or distribute any software that includes my code, that indicates you’ve agreed to the terms of the license, and if you don’t obey those terms, I can sue you.

This is the Linksys WRT54G wireless router. This was a hugely popular home router in the early 2000s; it cost $129, and Linksys had sold nearly half a million units in the first quarter of 2002.

In 2003, a guy called Andrew Miklas downloaded a copy of the firmware for the router, extracted the contents, and determined that the WRT54G was running the Linux kernel and a load of GPL software. Selling half a million routers definitely counted as “distributing software”, so if Linksys was complying with the terms of the GPL, they were legally obliged to make the source code available to anybody who’d bought a WRT54G router - but there was no mention of this anywhere on Linksys’ website, and no indication as to how customers could get the source code.

The reason this was so interesting was that the router firmware added support for whole bunch of wireless networking chips that previously didn’t work with Linux, and oh boy, the community wanted those drivers.

Now, the fun part: while all this is going on in, Linksys gets acquired by Cisco Systems, and Cisco find out they’ve got a problem. Linksys had bought all the wifi chips in the router from a company called Broadcom. Broadcom, in turn, had outsourced the firmware development to an overseas developer, who had somehow failed to tell anybody the firmware they delivered was built on Linux and GPL code.

Cisco’s response to all this was “this wasn’t our fault, but we accept it’s our responsibility, and we’ll publish the source code, just give us time to figure out the details”. Now, there’s a detail here that I can’t quite figure out from what’s available online. The source code for the Linksys WRT router was definitely published online in 2003. That release formed the nucleus of a project called OpenWRT, a GNU/Linux distribution for embedded devices - and in the process, it turned the Linksys WRT54G into one of the most popular devices in history, because thanks to the OpenWRT project, it wasn’t just a wireless router any more: it was a hundred-dollar headless Linux computer with a wireless chip and a four-port network switch.

So we know the code was published in 2003. We also know that in 2003, the Free Software Foundation began working with Cisco to help them achieve GPL compliance, and that five years later, the FSF ran out of patience and filed a lawsuit against Cisco Systems regarding the use of GPL software in Linksys devices. The lawsuit and the date of the filing is a matter of public record: what I couldn’t figure out is exactly what happened in the intervening five years.

My hunch is that Cisco was publishing the odd release here and there and hoping the whole thing would blow over, and the FSF were getting frustrated by the apparent lack of progress… but whatever the circumstances, it was the first time the Free Software Foundation made it as far as actually taking legal action, and in May 2009, the case was settled out of court, with Cisco appointing a compliance director, committing to make the full source code available for any product which used GPL, and making an “undisclosed financial contribution” to the FSF.

An out-of-court settlement like this is normally a pretty good indicator that a bunch of lawyers has sat down and said “look, you MIGHT not win this” – but it’s not as good as an actual judgment. The only instance I could find of the GPL actually making it as far as a court verdict was in Germany: in 2006, Harald Welte, a free software evangelist who had contributed code to the Linux kernel, filed suit against D-Link for selling a networked attached storage device based on Linux without making the source code available. The Frankfurt District court ruled in Welte’s favour, confirming the validity of the GPL under German law; D-Link was ordered to pay Welte’s costs, and to stop distributing the device in question. Whether they did or not I have no idea.

Of course, at the dawn of the “open source” movement back in 1998, none of this had happened yet, but it was pretty clear that it might, and that made a lot of people, and companies, extremely wary of the GPL: Steve Ballmer said in 2001, when he was CEO of Microsoft, that “Linux is a cancer that attaches itself in an intellectual property sense to everything it touches. That’s the way that the license works.”

Ballmer was wrong - that’s not how Linux works, that’s not how the GPL works, and that’s not even how cancer works - but when it came to public perception, that didn’t matter. Microsoft at the turn of the millennium believed the future was about selling desktop software: Windows, Office, Exchange, SQL Server. Computing belonged on the desktop, the desktop belonged to Microsoft, and anything that threated that dominance was a threat to Microsoft’s very existence.

That has changed dramatically, and I think the reason for that is one word: cloud.

The cloud changed everything, because it unlocked a whole new kind of revenue stream for companies that wanted to make money out of software: pay-as-you-go computing. And, in the process, it enabled economies of scale we’d never even imagined before.

During the early 2000s, my job title was “webmaster”. I built and ran entire websites: HTML, CSS, graphics, Linux, Apache, MySQL, right down to physically building the server that it would run on and plugging it into the network. I had a network crimping tool and a Photoshop license and I used both of them at least once a week.

If you’d asked me to host, say, a MySQL database for you… I could do that. I’d charge you a thousand pounds for the hardware, another thousand for my time to install it, set it up, plus maybe two hundred quid a month to cover power, internet, and support. I ran a few systems like that. They were what we call snowflake servers, because no two were alike. It was a fun way to make a living and you got to play around with cool toys - but it didn’t scale; if I suddenly got twenty new clients all wanting a MySQL database by the end of the day? Not a chance. Sorry.

But… scale that up by a factor of a thousand. Forget building servers. Build datacentres. Automate every single detail: operating system, networking, firewall, application stack, security, configuration, backup… now you go to all my clients and say “hey, you know we can give you a MySQL database in THE CLOUD and it’ll only cost £50 a month”? And before you know it, you’re raking in a few million quid a month just for hosting MySQL databases…

Friends, let me tell you the story of Sammy the Squirrel. Sammy lived in the forest, among all the other happy little woodland creatures. Every Sunday morning, all the woodland folk would gather in the clearing by the old oak tree and show everybody else what they’d been working on. And Sammy liked to write video games. Just for fun. One week, Sammy turned up with a new game they’d been working on: Acorn Adventure. It was brilliant. You play a curious little squirrel, running around the forest gathering acorns for the winter… just, lovely stuff. And Sammy was quite happy to give away copies for free, hoping the other woodland folk would take their game and add their own characters, and levels, or use it to create completely new games.

Next week, when Sammy arrived in the clearing for Show and Tell, they noticed that Jeff the Raccoon had got there early - and Jeff had brought an arcade machine! A proper old-school arcade cabinet, with shiny graphics, and buttons, and a joystick… and it was running Acorn Adventure. This was AWESOME. Sammy’s game, running on a proper arcade machine - and only 50 cents a play! Before long, all the woodland folk were queuing up to play; some of the smaller animals were pestering their parents for money so they could have another go, they were competing for high scores…

The following week, Jeff the Raccoon showed up in a shiny brand new pickup truck, with TWO arcade machines. The woodland folk just couldn’t get enough of Acorn Adventure… and for Sammy, the thrill of seeing everybody lining up to play their game wore off pretty quick. Especially once the animals started to complain. “It’s too hard to beat the owl on Level 2!” “You need better graphics!” “The music sucks! fix it!”

Sammy tried, patiently, to explain that Acorn Adventure was free software and they were welcome to contribute to it… but of course, it wasn’t free. The rest of the animals were paying fifty cents a game. As far as they were concerned, they were paying customers. And, well, winter was coming and Sammy had been so busy working on Acorn Adventure that they’d not had time to gather enough actual acorns, and with the cost of living crisis and everything Sammy was thinking wouldn’t it be nice if they could maybe make a bit of money from their game?

Next week, Jeff the Raccoon showed up for Show and Tell in a solid gold helicopter.

Sammy was there, as usual, and Sammy had brought along something new: Acorn Adventure 2.0! They’d improved the graphics, and added better music, and made it easier to beat the owl… and they’d also made a new rule: Acorn Adventure 2.0 was still completely free. You could take it home, play it, modify it, make your own levels - but if you wanted to install it on a pay-to-play arcade machine, you had to pay Sammy a dollar so they could buy enough acorns

Ooooh. The woodland animals were not happy about that… it all kicked off. Screeching and howling and frothing at the mouth and throwing rotten vegetables and saying Sammy was a traitor and a sellout and all sorts of terrible names, and one of them got so angry they took the code for Acorn Adventure 1.0 and renamed it EatDeezNuts.

Or… maybe that’s not what happened. Maybe when the angry mob show up at Sammy’s table demanding better graphics and new levels and more features… maybe at that point Wilbur the Weasel shows up and offers to help. Just a few small things at first: some new artwork here, a bit of music there, a bugfix in the high score table. Then more: Wilbur’s added a completely new level or two, new characters, a new graphics engine… Sammy’s sort of losing track of all the changes, but hey, that’s the beauty of free software, right? One feature all the animals have been asking for is electronic payments, so they can pay using PayPal instead of carrying bags of coins around… and sure enough, Acorn Adventure 3D lets you connect your PayPal account. All the woodland folk are getting really excited about Acorn Adventure 3D, every video arcade in the forest is ready to install the new version… then one of the play-testers notices something weird. The PayPal screen isn’t a real PayPal screen. It looks like one, sure… and it does actually connect to PayPal… but it’s also sending copies of everybody’s email and password to an IP address in Belarus. Turns out Wilbur’s new payment system isn’t exactly what it claims to be… but Wilbur’s vanished, and so has the mysterious mob of angry animals that put so much pressure on Sammy in the first place… and now you come to think of it, you hadn’t really seen any of them around before…

Free and open source software has succeeded in ways that we couldn’t imagine back in the 1990s. Back when folks first started talking about “open source”, the best that anybody realistically expected was to take maybe ten percent of a computing market that ran on desktops and was dominated by Microsoft Windows. The idea that there would be multiple trillion-dollar corporations built around free software - not to mention a modified Linux kernel in literally billions of Android mobile devices? Unimaginable.

But that’s where we are today. Companies like Amazon and Google are turning over billions of dollars in revenue every year, and a substantial part of that revenue comes from free software - and, in many case, doing so thanks to a very specific part of the GNU Public License which says that if your users are only interacting with a program’s output across a network, that doesn’t constitute distribution.

The Free Software Foundation wised up to this a long while ago, and created what’s known as the Affero GPL - Affero was the company that collaborated with the FSF on the wording, and the first organisation that published code under that license, way back in 2002. It’s basically the GPL version 3, with an additional clause which says that even if you don’t actually publish software, you’re required to make full source code available to anybody who interacts with your code across a network.

Now, this brings up a really interesting scenario. Lot of developers out there are using tools like Copilot and ChatGPT… and those tools have been trained on public code, including code published under the Affero GPL.

When you use code to train a language model, should the output of that model be considered a derivative work? There’s one argument says yes, obviously, how can it possibly be anything else? There’s another argument says no, don’t be stupid, that’s like every songwriter who’s ever listened to “Sweet Child O’ Mine” is ripping off Guns’n’Roses.

Maybe it depends on whether Copilot is regurgitating actual chunks of AGPL code, or generating original solutions using a model that incorporated AGPL code into its training set.

But… if it is a derivative work, then every company in the world that’s running any kind of platform as a service: Google, Facebook, Warcraft, Netflix… if even one of your employees has used Copilot to create code that’s part of that platform, you’re now legally required to make the entire source code to your platform available to anybody who uses it.

Over the last 20 years, though, the shift has been away from licenses like the GPL and towards what are known as permissive licenses: the Apache license, the Berkeley Systems Distribution, or BSD, license, and the MIT license. The vast majority of open source projects today are published under one of these licenses. .NET, Ruby on Rails, Android, nodeJS, Angular, React, Kubernetes.

If you want to understand the exact legal minutiae of these licenses, hire a lawyer; for the purpose of this talk, we can assume they all say basically the same thing: “this code is ours, we own the copyright, you can do just about anything you like with this code, except you can’t remove our copyright notice from it, and you can’t sue us if it doesn’t work”

These permissive licenses grant a considerable degree of freedom… and paradoxically, that often includes the freedom to take that freedom away. If you want to contribute some code to React, you have to sign a contributor license agreement which transfers your copyright to Meta Platforms Inc. If Meta then decides that React version 20 is going to be a commercial, closed-source product that costs ten thousand dollars, they can: you gave them permission to do that with your contribution when you signed the CLA.

So… why do people contribute to open source if they have to sign away their ownership to do so?

In a lot of cases, it’s because they get paid. The vast majority of code in the .NET runtime was written by Microsoft employees: they get paid a salary to write code, the code they write belongs to the .NET Foundation, the Foundation publishes it under an MIT license, everybody wins… right? Many of the core contributors to PostgreSQL actually work for Amazon, most of the folks who contribute to React work at Facebook. These are all companies with shareholders: they have a legal obligation to those shareholders to make profit, and so at some point they must have sat down with a bunch of lawyers and a bunch of spreadsheets and decided that open source was a good way to do that.

I do think some folks honestly do it for fun, or for the ego boost – which is fine, as long as your ego boost doesn’t end up as a critical component in somebody else’s banking system.

But then there’s the folks who contribute to open source because they think it’ll eventually make them some money. There was this lovely idea floating around for a long while that, hey, let’s all give our code away for free, and then people can look at the code, and use it, and see how amazingly wonderfully good it is, and then they’ll hire us! Or they’ll pay for a support contract, or they’ll hire us to provide some training, or they’ll buy a corporate license just because they’re honest, decent folk who want to do the right thing…

Didn’t quite work out that way, did it? The world we live in is full of Sammy Squirrel developers trying to stockpile enough acorns for the winter while Jeff the Raccoon flies around in his solid gold helicopter that he made by selling free software.

Within the last few years, we’ve seen a bunch of projects switch from permissive licenses to some sort of dual licensing model: MongoDB, ImageSharp, Docker, Terraform, Unity, and most recently Redis. Redis is a hugely popular in-memory cache database. It’s been around for fifteen years, it’s written in C, it’s blisteringly fast, and until March 2024, it was published under the BSD license.

In March, Redis announced that they were switching their licenses. Future versions would no longer be distributed under the BSD license, and Redis went so far as to explicitly state that “cloud service providers hosting Redis offerings will no longer be permitted to use the source code of Redis free of charge” - and, sure enough, the woodland folk didn’t like that one bit. Within days, a new community project, Valkey, had sprung up, based on a fork of the latest BSD license of the Redis codebase. Microsoft announced Garnet, a new key/value store which is protocol compatible with existing Redis clients.

I have no idea what the future looks like for projects like Redis and Terraform. I strongly suspect that the open source projects started in response to those license changes - Valkey for Redis, OpenTofu for Terraform - will do well for a year or two, and then they’ll go through the same reckoning as the projects which spawned them: success means more users, more users means more bug reports and feature requests, and unless lots of users also means lots of money, sustainability becomes a problem.

Switching to hybrid licensing isn’t a new idea, though. There’s a .NET library called ServiceStack, which I used to work with a lot: about ten years ago, ServiceStack was streets ahead of the rest of the .NET ecosystem when it came to building web services and REST APIs. Then in 2013, ServiceStack announced that their next release, 4.0, would switch from a BSD license to a dual licensing model. ServiceStack’s was created by a guy called Demis Bellot, who was working as a developer at StackExchange; he said at the time it was “sink or swim” for ServiceStack: either he had to figure out a way to make it pay the bills so he could quit his day job, or he had to shut the project down.

And, yes, that’s why I stopped using it. Going from free-as-in-beer to a thousand dollars per developer turned it into an argument I couldn’t win: the company I was working for didn’t actually make any money from APIs - not directly, anyway - and so we switched to a different framework instead of paying for ServiceStack.

Some of ServiceStack’s users switched to other platforms. Some paid for licenses. Some decided to stick to the forked the last BSD version of the codebase and created a new project called NServiceKit, which made a big song and dance about how important it was that it didn’t cost any money.

When I was researching this talk, I emailed Demis to ask: it’s been ten years: how’s it all going? Here’s a few quotes from his response:

“I’ve been able to work full time on ServiceStack ever since leaving StackExchange. A decade of development later, the ServiceStack software itself has greatly improved and is much more capable than what was possible as a side OSS project.”

“I was willing to take a significant pay cut to be able to work on my own projects so was pleasantly surprised when it ended up making more money than any job I had prior.”

“ServiceStack has allowed our family to be financially independent and given me the freedom to work on whichever features I want.”

I don’t know about you folks, but financial independence and the freedom to work on whichever features I want sounds to me like a pretty good deal.

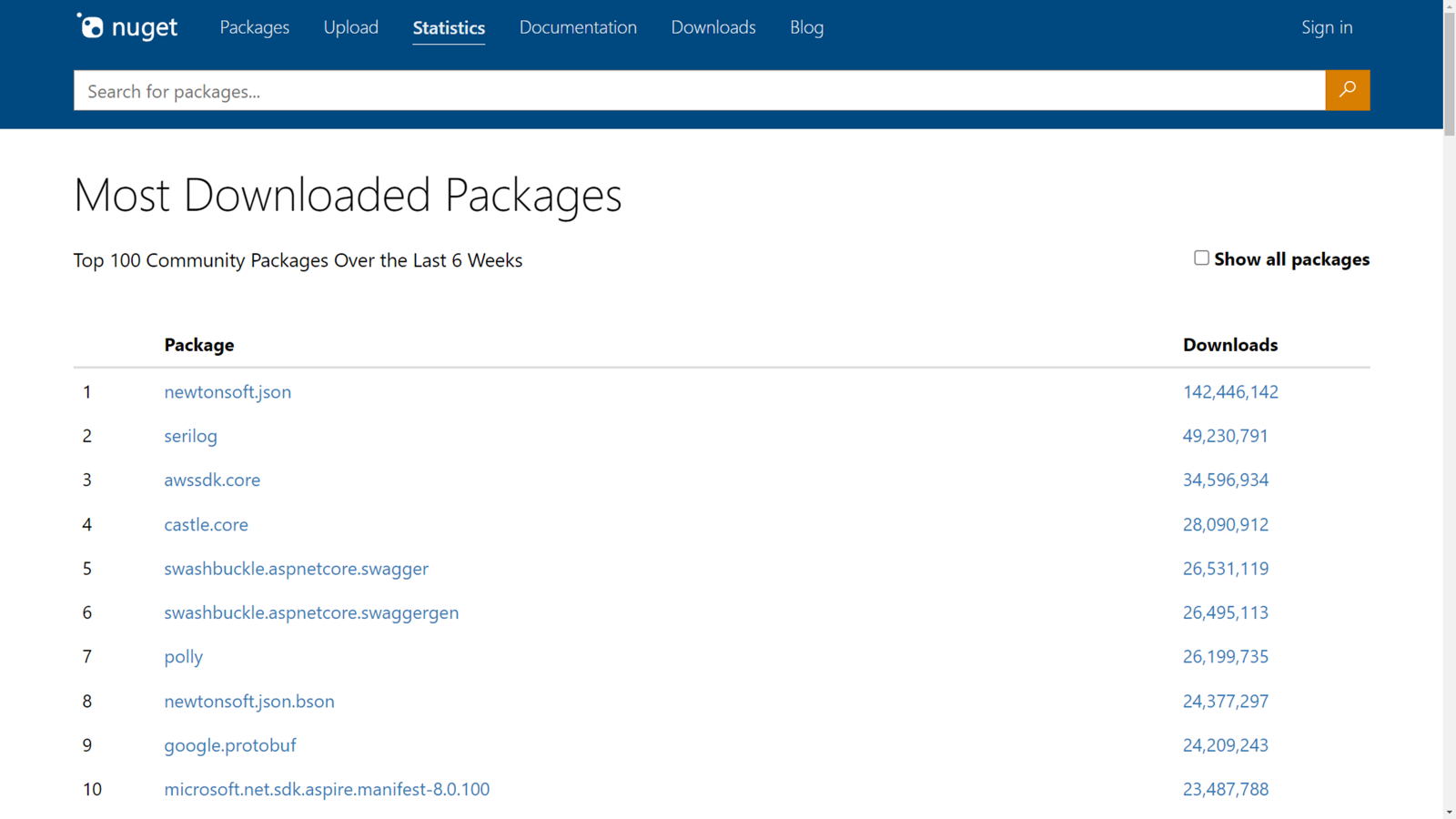

ServiceStack is on version 8 now, and has been shipping new releases and features pretty steadily since they switched licenses. And what happened to NServiceKit? For a while, it looked like it might get some traction… but after about a year, it kinda fizzled out. The project is still up on GitHub: the last commit was 9 years ago, and the README still talks about joining their Google+ Community.. you remember Google+, right? And if we look at the package download stats on NuGet: ServiceStack’s tracking at around 12 million downloads, NServiceKit’s had less than 250,000.

So, in the case of ServiceStack at least, free software works a lot better when you can get people to pay for it.

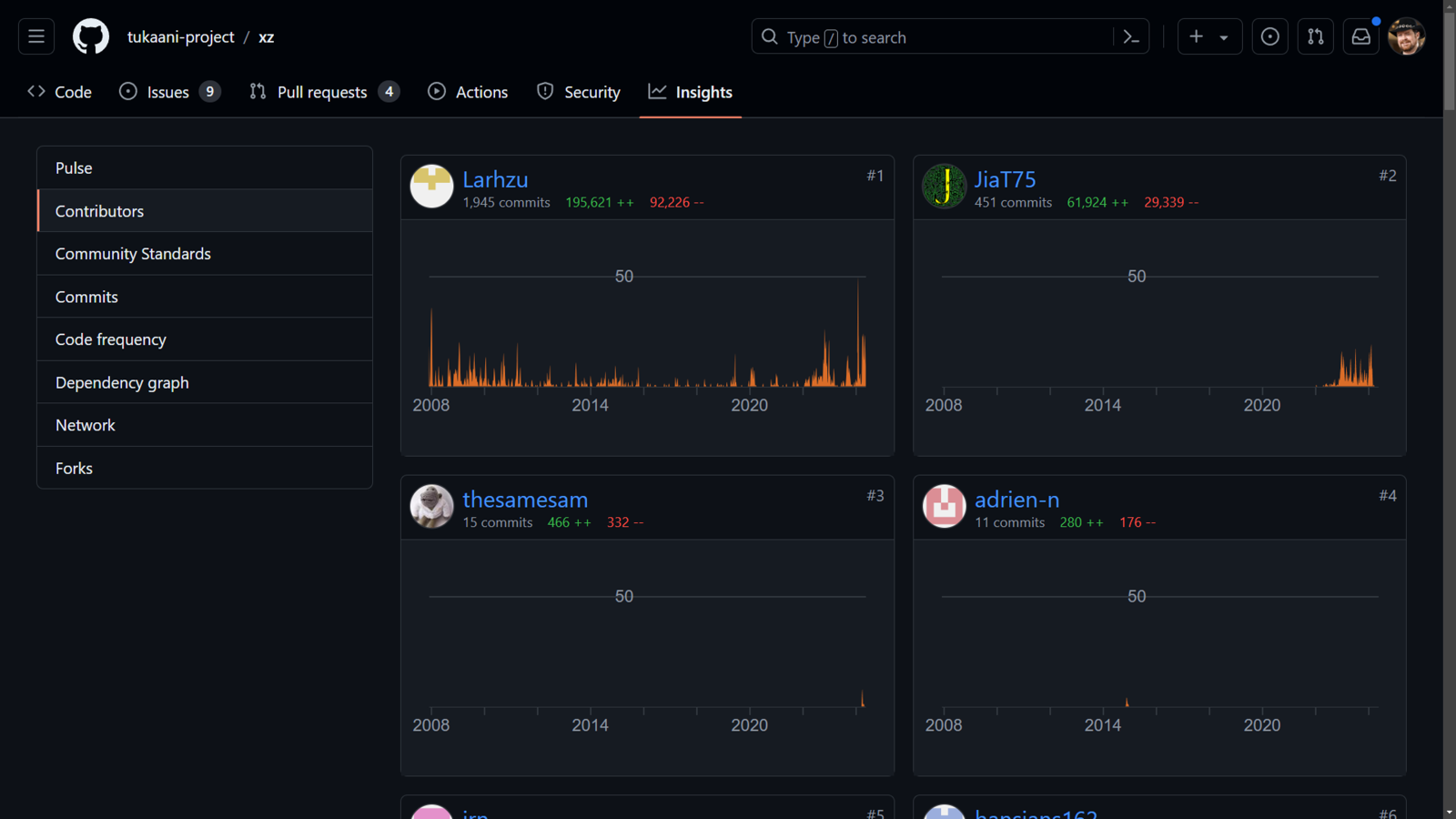

And, of course, our friend Wilbur the Weasel wasn’t a weasel at all… it was a person, or maybe a group of people, who came incredibly close to smuggling a security backdoor into several major Linux distributions. The project in question was a Linux compression library called xz - or xz if you’re speaking American; xz is used in several key parts of Linux, including the openssh server used to provide remote access to… just about every Linux machine on the planet. You know what sort of well-funded, well-resourced development team was responsible for this vital piece of our society’s digital infrastructure? That’s right!

Here’s the contributor dashboard for the xz-utils project. The top contributor is Lasse Collin, larhzu, with 1,945 commits since 2008. The #2 is somebody called JiaT75: 451 commits. #3 is TheSameSame, with 15 commits, and the fourth most active contributor to this vital piece of internet infrastructure is Adrien-n, who made 11 commits to the project in 2014.

So in June 2022, when people on the xz-devel mailing list started hassling Lasse for being too slow to merge patches, it’s no wonder that they gratefully accepted Jia Tan’s offer to become a co-maintainer. Nearly two years later, a completely random stroke of luck led Andreas Freund, a developer working at Microsoft, to discover that Jia Tan had managed to implant an extremely serious security backdoor into the binary distributions of xz… the vulnerability itself was an incredibly sophisticated series of patches and changes, all designed to avoid detection, but the access required to make those changes in the first place was obtained by social engineering - and it was that pressure, one underfunded, overworked person feeling like they were responsible for such a critical piece of infrastructure, which made them vulnerable to the social engineering attack in the first place.

Software works better when the people who create it aren’t worrying about paying their bills. Most of the developers I know - and, I suspect, most of the people in this room - if money wasn’t a factor, they’d find interesting problems to work on, and they would create really good solutions to those problems. But writing good software takes time, and time is money, and that brings us right back to the gritty heart of the problem: if you’ve already given something away for free, it is incredibly difficult to turn around charge for it afterwards. You’ll lose a lot of users in the process - some because they legitimately have no money, some because they feel like you cheated them, some because actually it turns out whatever business they were running was only profitable because your generosity was bigger than their profit margins. You’ll get a lot of negative reactions and bad noise, and so you end up here: you did a nice thing, you shared it with the world, other people used it to get rich, and now everybody hates you.

Now, I’m going to say this, and I’m going to say it very loud, and I want everybody here to think about it, and write it down, and retweet it, and I want you to print this out and stick it on the back of your bathroom door so you see it every time you’re on the can, and I want it to be the first thing you think about when you wake up in the morning and the last thing you think about when you go to sleep at night:

PEOPLE WHO SHARE THEIR SOURCE CODE DO NOT OWE YOU ANYTHING.

If you build your project, your product or your business on free software, you get the code, and a guarantee that nobody can turn around afterwards and stop you from using it. You are not entitled to support. You are not entitled to patches. You are not entitled to security updates. You are not entitled to a free upgrade to the next version, you should not even rely on the fact that the code will still be online tomorrow. If any of those things is important to you, you should be prepared to pay for them - whether you buy a support contract from the developers, or hire somebody else to maintain your own copy of that code.

All you get is the code, and the guarantee that they won’t stop you. And it astonishes me that for a lot of people, that’s not enough. I use Adobe Creative Suite a lot. I don’t have the code. I’ll never have the code. I have to pay them fifty bucks a month or that software will stop working. If I find a bug, I get to… file a support request and wait a week for somebody to tell me they don’t care. If Adobe turns around tomorrow and says Creative Cloud is now five hundred dollars a month… I can either pay it, or lose the ability to open my own projects. And if Adobe goes bankrupt and their authentication servers shut down? Well, now I’ve got ten years’ worth of Premiere and After Effects video project files that I can’t even open, let alone create any new ones. And people like Richard Stallman are out there going “well that’s your own fault for not using free software”… folks, Blender and The GIMP are not going to replace Adobe Creative Suite any time soon. Not even close. And let’s not even think about the fact that Blender and the GIMP sounds like a pilot for an really, really bad television show.

I love the ethos behind the Free Software Foundation. I love that the GNU Public License exists, and that something as powerful as Linux exists in the world thanks to that license, and that nobody can ever take that away. But there is obviously a huge gap between Linux and Adobe, and what we’ve been seeing since the 1990s, and we’re still seeing today, is an industry trying to figure out the most sustainable way to bridge that gap.

It seems to me like open source worked great when interest rates were low and shareholders were happy and there was free money sloshing around everywhere… and now everybody’s under pressure, whether you’re the CEO of a multinational dealing with your shareholders, or a solo developer standing in a grocery store wondering when the heck breakfast cereal became so damn expensive, and so we’re all trying to work out the same thing: when there’s money on the table, how can I make sure I get my fair share?

And on that note, I want to wrap up this talk today by giving you all something to think about, to take away and chew over in your brains and see where it leads you.

Think about music for a moment. We’ve seen a transition from vinyl and CDs, to illegal MP3s on services like Napster and Limewire, to legitimate downloads like the iTunes store, to streaming platforms like Spotify and Google Music. Spotify has 250 million paying subscribers. You know what those subscribers are paying for? Convenience. Fifteen bucks a month so that when they want a thing, they can have it. Licensing and ownership doesn’t even come into it. Very few people stop to worry about that any more: they just want THE THING NOW.

You know why the cloud works? Convenience. It’s like Spotify for IT infrastructure. You want to hear the new Taylor Swift album right now, except it’s not Tay, it’s a 64-core PostgreSQL cluster… the cloud got your back, baby. And you never actually own the thing; it’s not like when you’re finished using your 64-core PostgreSQL cluster you can sell it on eBay. But convenience rules, and companies love it.

Has anybody ever tried to get a big company to pay for anything? Any of you folks out there ever tried to get your employers to sponsor an open source project? It’s an absolute nightmare, isn’t it? And if you’re the project maintainer, trying to persuade somebody to give you a thousand bucks for software that they think they already own… well, that’s even worse.

But let me ask you another question: think about your company’s Azure bill this month? Or AWS, or Google Cloud, or GitHub? Do you know what you actually paid for? Probably not - and, yes, there’s a good chance a chunk of it is paying for free software because it’s easier than running it yourself. But imagine a new line item appears on next months’ bill: software packaging and delivery: ten dollars. Is your company going to quibble that? Or are they just going to go “welp, I guess that’s a thing we do now.” What if it was a hundred? What if it was a thousand dollars a month?

Now, we’re going to use NuGet as our example here, because it’s a platform I know very well. Let’s imagine for a second that NuGet wasn’t necessarily free.

Let’s start NuGet Premium. There’s a free quota, so casual users - individuals, hobbyists, students - they can just use it. But if your company is using CircleCI, or Azure DevOps, or GitHub Actions, to run a dozen builds a day? You’re going to blow through the free tier pretty quick… and then you’ve got a choice.

You can download the source code from, GitHub, compile it yourself, package it… but, y’know, effort.

You can set up a paid account. Pay monthly, credit card, just like folks do for Spotify and Netflix.

Or… we’ll stick it on your company’s cloud bill. Yes, this means coordinating with GitHub, and Google, and Amazon, and Azure, and there will be meetings, and contracts… but if you wanna change the world, you need to solve the hard problems. We’ll track of whatever metadata Github and Amazon need to pass those costs on to their own customers, and we’ll send them a big fat bill every month - and if they want to add twenty per cent to make it worth their while? Fine. Don’t care.

And then: we pay the package authors. Now, we’re not selling software here - any more than Spotify is selling music. We’re selling convenience, and since your code forms part of that service, we’ll give you your cut.

How much? Let’s work out some numbers.

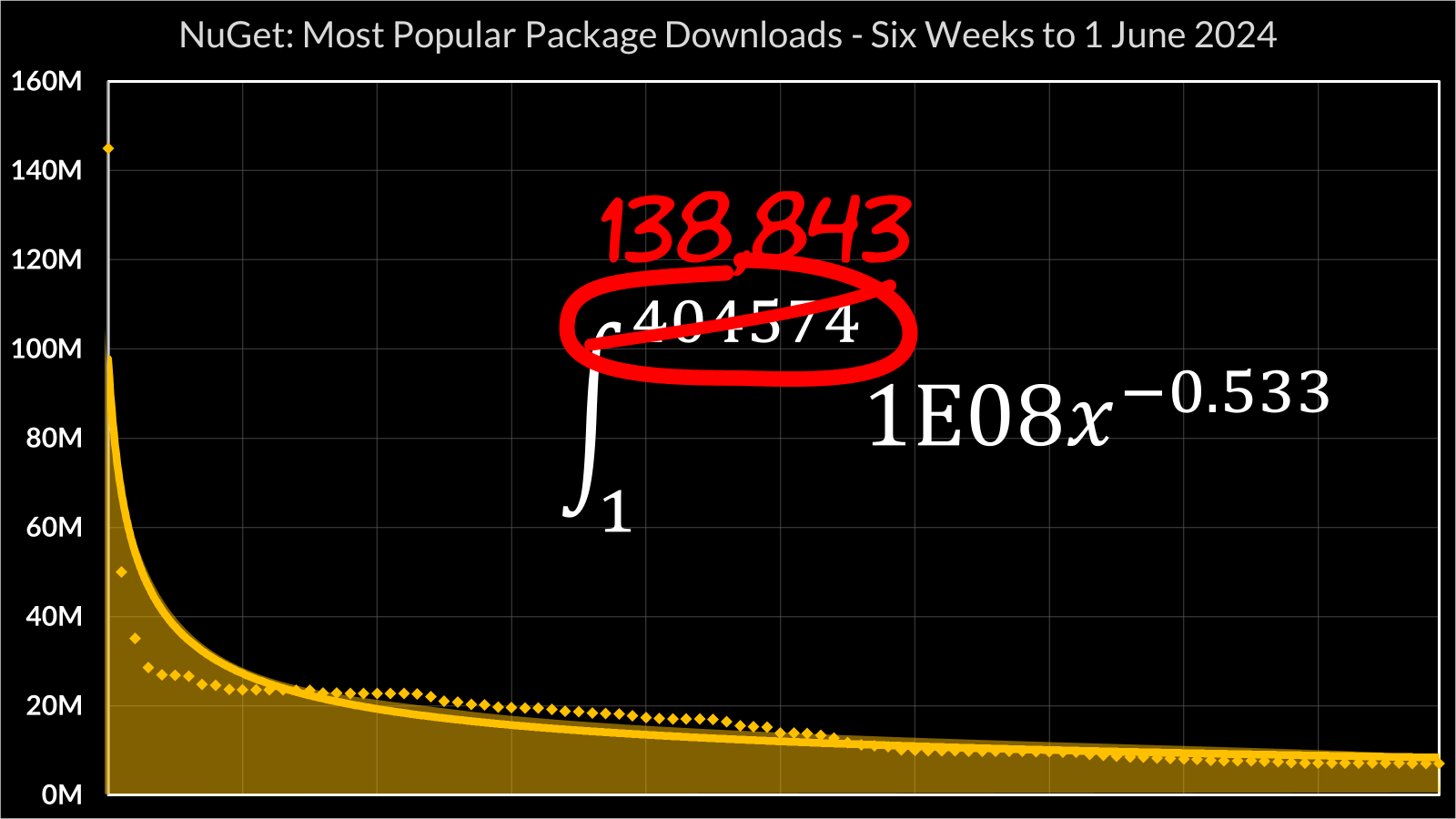

NuGet doesn’t publish total download figures, but they do publish download figures for their 100 most popular packages, so we can plot those figures on a chart, and use Excel to find a trend line for that data series. The equation for that line is here:

And if we can calculate the area underneath that line, all the way out to the 404,574th most popular package on NuGet, that’ll give us the total number of downloads. Time for some calculus…

But hang on a second… the whole point here is to support the work people are actually doing to maintain their open source projects. If we use this number here, we’re including recent downloads for every project on NuGet – including the ones that haven’t been touched since 2016. So let’s restrict this to just the packages which have had a release in the last 12 months.

That turned out to be way more complicated than I thought; I ended up writing some code to download the entire NuGet catalog into a local database; if you want to know how I did that, I’ll share a link to the code at the end. I queried that database for packages which had a release since 1st June 2023, and which have not been deleted: 138,843 of them.

Then, plugging that into Wolfram Alpha – you didn’t think I was going to do calculus by hand, did you? This isn’t high school, folks - and that gives us a number: 53 billion and something.

Next question: how many users are we talking about? This is where things get a bit fudgy… there’s no published data for this, so what I did is to add up all the downloads for the various versions of Newtonsoft.Json over six weeks, then assume the average NuGet user downloads Newtonsoft.Json about ten times a week, ‘cos that’s about how often I download it, and I’m obviously a very average person.

That gives us 2,374,102 active users. Let’s call it 2.4 million, make the numbers easier.

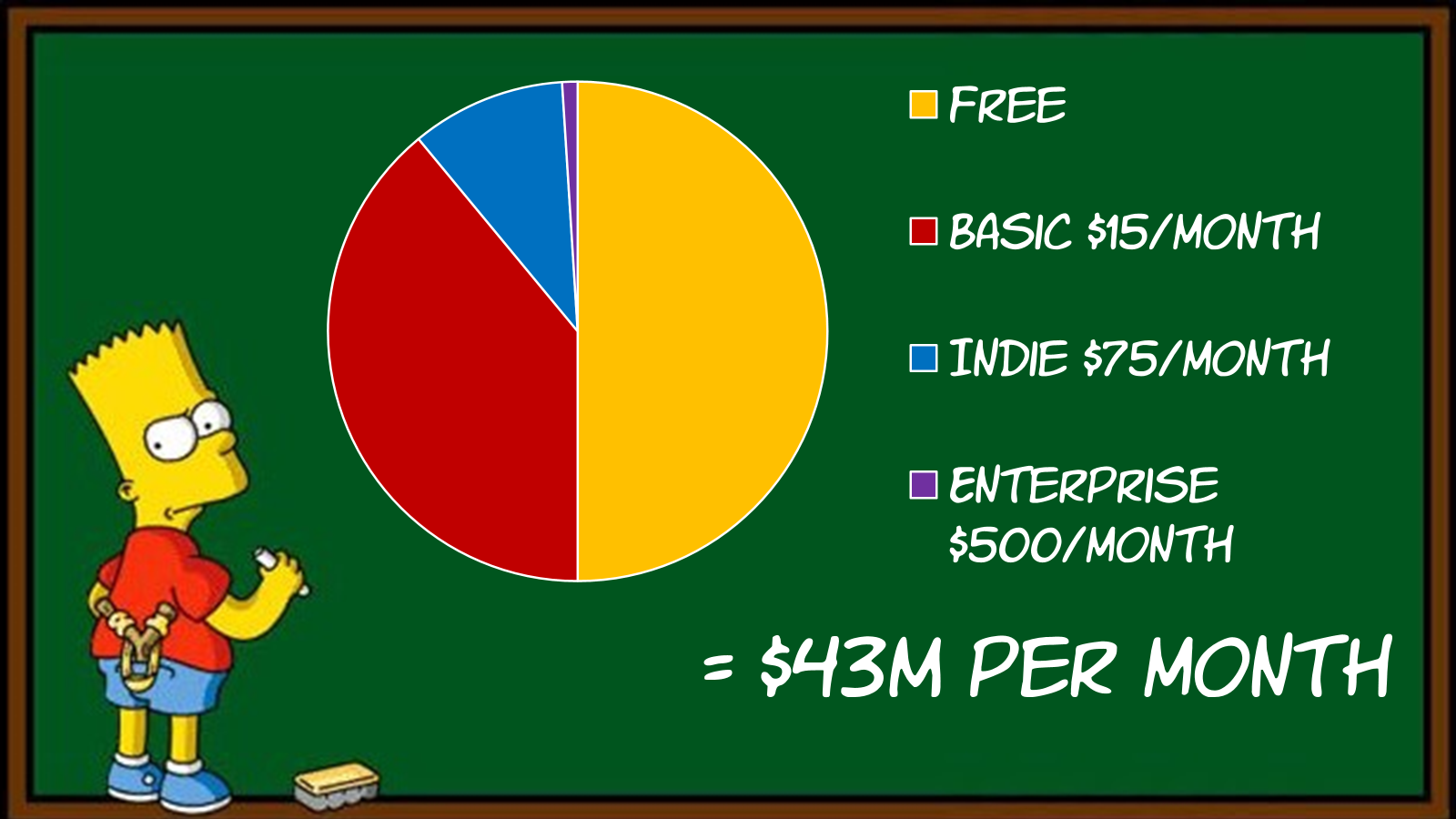

OK, here’s our baseline numbers. 53 billion downloads every six weeks is 40 billion downloads a month, or close enough. 2.4 million active users. Now, let’s invent a pricing plan.

Basic costs fifteen dollars a month. There’s an indie plan which is 75, and enterprise is 500. Assume half our users are on the free tier, 10% are indie, 1% are enterprise, the rest are basic.

That’ll bring in 43 million dollars a month. Let’s keep three million for snacks. Or, y’know, hosting and salaries and admin. But mainly snacks.

So there we go. 40 billion downloads a month, 40 million dollars a month… we can pay 0.1 cents per download.

Now, folks, this is not a business plan, although it might be fun to turn it into one. This is an experiment: I wanted to see if these numbers came out in the right kind of ballpark, and they do.

At the top end, the most popular packages like AutoMapper and Moq: they’re bringing in about thirteen thousand dollars a month. The kind of money that’ll support a full-time maintenance developer, maybe even a small team.

The middle tier, projects like ImageSharp? We’re talking the kind of money that justifies maybe spending a day a week on it, or taking a bit of time off work to focus on the next release.

And then way down the list, projects like Naudio… we’re talking a hundred dollars a month. Not much, but that’s a new dev laptop every few years, or a night out with your partner to make up for spending all weekend at your desk again.

This also doesn’t solve the fundamental problem of the economics of free software, which is that in a capitalist society motivated by profit, the winning strategy is not to reward altruism, it’s to exploit it. The line has to go up, and if the line stops going up and the shareholders find out you were being nice, that’s probably not going to end well.

Maybe, though, something like this could start moving the needle. Maybe it’s a step towards us all acknowledging that installing software components in two mouse clicks is a convenience worth paying for, even if the actual code doesn’t cost anything - and normalising the idea that the folks who created that package can expect to get paid when their work gets used.

Remember: all we’re talking about here is paying for convenience. Folks who subscribe to NuGet Pro don’t own the software, just like paying for Spotify doesn’t mean I own any Taylor Swift albums. We’re talking about Deliveroo for binaries: delivery service for code which is provided to you under whatever license the authors consider appropriate, whether that’s a paid license, a permissive open source license, the GPL, or it’s completely in the public domain. We’re doing the 2024 equivalent of charging ten bucks for a Red Hat Linux CD-ROM because downloading it over dialup is a pain in the ass.

Of course, this is never going to happen. Every mainstream development platform has a free package repository: NuGet, npm, maven, Ruby Gems… change any of those to a premium service and the woodland folk would riot.

But: within the next year or two, something very interesting is going to happen: WASI. The Web Assembly Systems Interface is a standardised set of APIs for composing software written in different languages - if anybody saw Steve Sanderson’s talk at NDC London in January? This could be a game-changer for the whole concept of interoperable software. You want to build an app in Go that uses a pricing engine built in Haskell and the Razor view engine from .NET? WASI will let you do that.

As soon as WASI goes mainstream, people are going to start building WASI components. WASI for doing JSON serialization. WASI for decoding JPEGs. WASI for rendering PDFs. And those components will be cross-platform: it doesn’t matter if you’re working in C# or JavaScript or Rust: if you need to decode a JPEG, that’s the library you use.

And so, inevitably, there will be the WASI equivalent of NuGet, or npm: a vast online library where everybody publishes their WASI packages so the rest of the world can install them and use them… so what if it wasn’t free?

Before we all rush headlong into another idealistic round of “yay free software is going to save the world!” and end up burned out and exhausted while Jeff’s flying around in a solid gold helicopter, let’s all take a moment to think about this.

Open source is 25 years old.

We’ve done free as in beer, and it mostly works. There are literally millions of people out there right now writing code, building apps and websites, making videos and music and art and connecting with each other using software that didn’t cost a single cent, and when those people are hobbyists and students and kids with no money, that’s awesome. But if you’re making a million dollars a year, you should be sharing that with the people who helped you get there.

We’ve done free as in speech, and that mostly works. There is a free, open operating system out there that nobody can take away, supported by a growing body of legal precedents which says licenses like the GPL are valid and legally binding… but that freedom has come at a cost. It’s frightening how much of the internet runs on projects maintained by a single person, in their spare time, and it’s horrifying how much aggression and abuse those maintainers have to put up with.

So maybe it’s time to think about a third kind of freedom. The freedom to wake up on a Saturday knowing that you can take the weekend off and not feel guilty about it. The freedom of knowing that your boss isn’t gonna WhatsApp you because your customers’ details have ended up for sale on the darkweb. The freedom of knowing that you’ve got enough money coming in to pay the rent, and that if you want to step down from maintaining your project, the folks who step up to take over will be doing it for the right reasons.

The freedom to unwind, unplug, get away from it all for a while, and not worry about what’s going to be waiting in your inbox when you get back.

Free beer and free speech are all very well, but a free weekend? That’s something worth paying for.

Thank you.